Oystercatchers: Learning how and where to survive

Wednesday, August 29th, 2012

Species: Oystercatcher

Project: Fine-scale foraging patterns of Oystercatchers in the Wadden Sea

As far as we know, adult Oystercatchers are extremely faithful to their wintering site, returning to the same site year after year, and some even defend pseudo-territories there (Ens & Cayford 1996; Goss-Custard et al. 1982). A major challenge for young Oystercatchers after fledging is learning to survive and finding a good spot to spend the winter for the rest of their lives. It is only after the young birds have become sufficiently proficient at surviving that they return to the breeding grounds (usually when three years old) for the next important step in their social career: acquiring a mate and a territory to breed (Ens et al. 1995). Studying the settlement decisions of the young Oystercatchers is extremely interesting, but also very difficult, and the UvA-BiTS loggers do not seem ideal, because contact is only possible within range of the wireless network. However, due to the growing number of scientists in the Dutch Wadden Sea who know the tricks of the trade, we now have some very nice data from a “settling” young bird carrying an UvA-BiTS logger.

On 2 August 2011 we caught several Oystercatchers with mist nets on the feeding grounds of the Balgzand tidal flats, where we also study the birds with a camera. [Fine-scale foraging patterns of Oystercatchers in the Wadden Sea]

We lost contact with a few birds over the course of winter, including an individual designated LB-LAGC. The last time we received data from the bird was on 18 November 2011. However, on 14 August 2012 the bird was spotted by Roeland Bom on Richel, a sandbar 40 km to the northeast of Balgzand. The Navicula, a research vessel from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), transported a mobile base station to Roeland, and in the course of several days he managed to extract all the information from the bird. Below is the story that emerged.

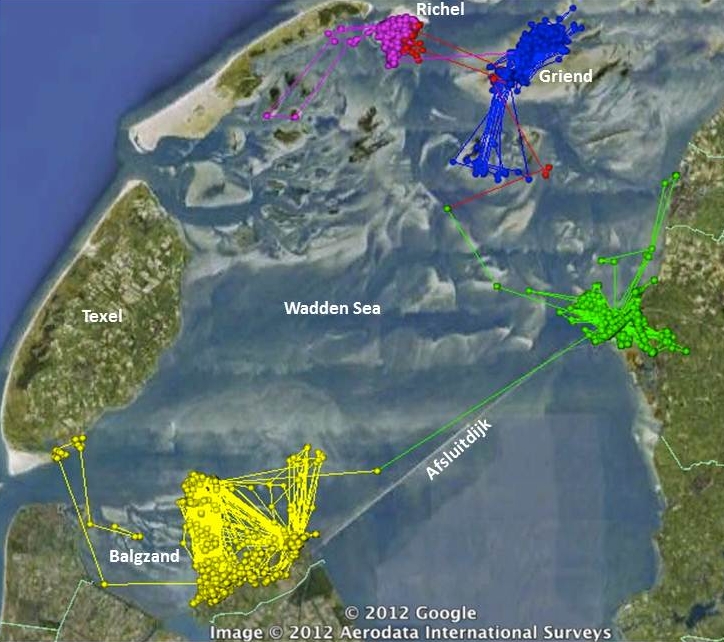

When LB-LAGC was caught and marked on 2 August 2011 it was diagnosed as a bird in its second calendar year, i.e., approximately one year old. It never returned to the low-tide feeding area where it was caught (the closest it came was 3 km), but remained to feed and roost on the eastern part of the Balgzand. It left the Balgzand area on 30 November 2011 and moved 30 km to the northeast. The figure below shows the areas that it subsequently visited and also lists the dates that these areas were visited.

| Date range | Location | Color |

| 2 Aug 2011 – 30 Nov 2011 | Balgzand (confirmed by visual observations – Wim Tijsen on 4 and 9 September 2011) | yellow |

| 30 Nov 2011 – 28 Mar 2012 | Afsluitdijk dam near Kornwerderzand (confirmed by visual observations – Dirk Kuiken on 15 February 2012) | green |

| 28 Mar 2012 – 31 Mar 2012 | Richel, short stop on Griend when moving from Kornwerderzand to Richel | red |

| 31 Mar 2012 – 24 Jul 2012 | Griend | blue |

| 24 July 2012 – 23 Aug 2012 | Richel (confirmed by visual observations – Roeland Bom on 14, 15, 17-19 August 2012) | magenta |

.

After leaving Balgzand the bird visited three different areas: Kornwerderzand, Griend and Richel. Basically, the bird spent in each case many weeks in the same area measuring a few square kilometers. Maybe that is the time needed to obtain a good estimate of the quality of the feeding area. However, the quality of the area also depends on the pressure of conspecific competitors. In the Exe estuary, young birds move to the best mussel beds when the competitively superior adults are away to breed, but most move off again when the adults return at the end of summer (Goss-Custard et al. 1982). Thus, it is possible that the young birds learn the location of good feeding areas in summer and experience the pressure of competitors in winter. Our bird spent its first summer and part of its second winter on Balgzand, but decided to move on. It spent its second summer on Griend, but moved on to Richel at the end of July, the time that the adult birds return from the breeding grounds. Maybe feeding conditions around Griend were good as long as there were not too many competing adults. So far, our bird hasn’t spent a full summer and full winter in the same place and clearly hasn’t settled. It would be great if we could keep track of this bird and see where and when it finally settles. And if it didn’t really settle, that would be very interesting to know too, as we would need to add a “gypsy” strategy to the possible career strategies of the Oystercatcher.

References

Ens, B.J. & Cayford, J.T. 1996. Feeding with other Oystercatchers. In: The Oystercatcher: From Individuals to Populations (Ed. by J.D.Goss-Custard), pp. 77-104. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ens, B.J., Weissing, F.J. & Drent, R.H. 1995. The despotic distribution and deferred maturity: two sides of the same coin. The American Naturalist, 146, 625-650.

Goss-Custard, J.D., Durell, S.E.A.L. & Ens, B.J. 1982. Individual differences in aggressiveness and food stealing among wintering Oystercatchers, Haematopus ostralegus L. Animal Behaviour, 30, 917-928.

Goss-Custard, J.D., Durell, S.E.A.L., McGrorty, S. & Reading, C.J. 1982. Use of mussel Mytilus edulis beds by oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus according to age and population size. Journal of Animal Ecology, 51, 543-554.

Latest Highlights

Overwintering and foraging areas used by a 24-year old Eurasian spoonbill

Wednesday, April 18th, 2018

Lesser Black-backed Gulls from Schiermonnikoog enjoy their winter holiday

Tuesday, April 3rd, 2018

Oystercatchers returning from inland breeding grounds

Sunday, July 23rd, 2017

GPS tracker with SMS messaging

Monday, November 2nd, 2015

Ronny found back, three years after deployment of the UvA-BiTS GPS-tracker

Wednesday, July 8th, 2015

Lesser Black-backed Gulls feed on potato crisps in Moeskroen

Wednesday, November 13th, 2013

‘Vogel het uit!’ has won the 2013 Academic Year Prize

Tuesday, November 5th, 2013

Back in Europe: UvA-BiTS Honey Buzzard photographed at the Strait of Gibraltar

Wednesday, May 15th, 2013

UvA-BiTS database passes 10 million record mark

Wednesday, May 8th, 2013

Gulls pouring into the Kelderhuispolder colony

Wednesday, April 17th, 2013

To the Karoo and back: Mate replacement & GPS tracking study of an ousted eagle

Monday, March 25th, 2013

Meeting Montagu’s Harrier Edwin in Senegal

Wednesday, March 20th, 2013

Oystercatchers: Learning how and where to survive

Wednesday, August 29th, 2012

New GPS mini-tracker facilitates investigation into movement of smaller animals

Wednesday, July 4th, 2012

Over 5 million GPS fixes in the UvA-BiTS database

Thursday, June 21st, 2012

Tagged Lesser Black-backed Gulls return to Orford Ness

Wednesday, April 18th, 2012

Gulls spotted in their over-wintering areas

Wednesday, December 21st, 2011

The UK a top vacation destination in 2011

Wednesday, July 13th, 2011

A long way from home

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

Visiting Amsterdam for a day

Saturday, May 14th, 2011

Female deserts brood, male raises chicks

Friday, May 13th, 2011

Wintering range in Sierra Leone

Friday, May 13th, 2011

Camera watches foraging Oystercatchers day and night

Thursday, May 12th, 2011

The return of a bird presumed dead

Wednesday, May 11th, 2011

Texel gulls back from wintering areas

Sunday, May 1st, 2011

First Lesser Black-backed Gull returns to the breeding colony

Monday, April 13th, 2009