Overwintering and foraging areas used by a 24-year old Eurasian spoonbill

Wednesday, April 18th, 2018

Species: Eurasian Spoonbill

Project: How does habitat quality determine the breeding success and survival of Wadden Sea spoonbills?

Werkgroep Lepelaar, a research team from the University of Groningen and the NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, has been tagging adult and juvenile Eurasian spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia leucorodia) with UvA-BiTS GPS tracking devices since 2012 to follow the birds’ movements while breeding, feeding and migrating. The team also places color-rings and takes measurements from spoonbills on the Dutch Wadden Sea Islands every year. Re-sightings by hundreds of volunteers all along the flyway show their migration routes and wintering sites.

Map of the spoonbill migration system. The sizes of the dots represent the number of individuals in the analysis that wintered at each site. (From Lok et al. 2015)

The team is hoping that GPS data from the tagged birds will shed light on why spoonbills experience higher adult mortality during the spring migration. Spoonbills that breed in the Netherlands during the summer migrate different distances (approximately 1000, 2000 and 4500 km) to winter in France, Iberia and Mauritania, respectively. Research done between 2005 and 2012 showed that mortality during spring migration was much higher (18%) for the birds that reached Mauritania, compared with those wintering in France (5%) or Iberia (6%) (Lok et al. 2015). The increased mortality observed during the long migration back from Africa may be due to suboptimal foraging areas and unfavorable weather conditions as the birds return to northern Europe along the western edge of the Sahara Desert. These conclusions are fascinating since previous observations of ringed spoonbills indicated that the birds are highly site faithful when choosing wintering areas, especially older individuals (Lok et al. 2011).

The story of the migration of a spoonbill that was tagged in April 2016 by Werkgroep Lepelaar is particularly interesting. The metal ring on spoonbill #6284 indicated that she hatched in summer 1994 on Schiermonnikoog Island in the Netherlands, in one of only 22 clutches on the island for that year, which now makes her 24 years old. During the 2017 breeding season on Schiermonnikoog, she chose a tagged male as a partner and went on to have a young chick that has also been GPS tagged.

Tagged spoonbills in the Guerande salt marshes of western France in January 2018 (Photo by Joel Fievre)

In September 2017, while her young continued to hang out on the eastern coast of Schiemonnikoog, 6284 started her trip south during the first quiet evening after an autumnal and stormy week. After one and a half days of flying (with an evening stopover in the Slikken van Flakkee along the southern Dutch border), she arrived in Baie D’Arcachon in France. This area is frequently used by spoonbills as a stopover, but is not considered a popular wintering area. From there she continued on to overwintering grounds in southern Spain.

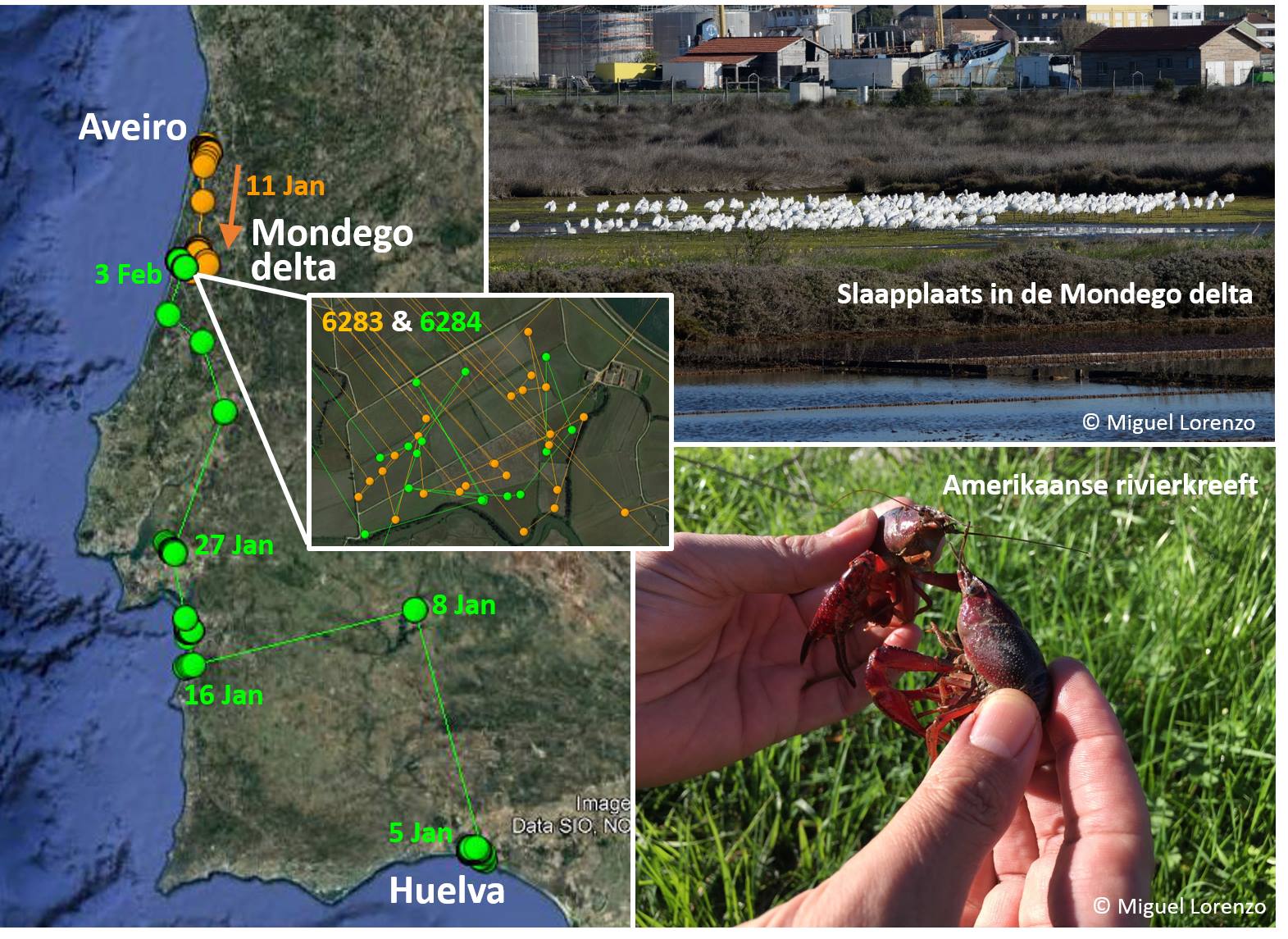

The GPS tracking data indicates that 6284 spent the winter of 2017-2018 in southern Spain. In February 2018, she was spotted several times as she travelled over 500 km north from Huelva in southern Spain to the Mondego Delta in Portugal. She probably made the trek to forage on American crayfish, a favorite prey of spoonbills. But why didn’t this seasoned veteran just stay there all winter? For now, that remains a mystery.

Left: GPS tracks of spoonbills 6283 and 6284 on the Iberian Peninsula in January and February 2018. Top right: Spoonbill resting area in the Mondego Delta in central Portugal. Bottom right: American crayfish, a favorite prey of spoonbills.

References

Lok T, Overdijk O, and Piersma T. 2015. The cost of migration: spoonbills suffer higher mortality during trans-Saharan spring migrations only. Biol. Lett: 11. 20140944. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.0944

Lok T, Overdijk O, Tinbergen JM, and Piersma T. 2011. The paradox of spoonbill migration: most birds travel to where survival rates are lowest. Animal Behaviour 82: 837-844

Latest Highlights

Overwintering and foraging areas used by a 24-year old Eurasian spoonbill

Wednesday, April 18th, 2018

Lesser Black-backed Gulls from Schiermonnikoog enjoy their winter holiday

Tuesday, April 3rd, 2018

Oystercatchers returning from inland breeding grounds

Sunday, July 23rd, 2017

GPS tracker with SMS messaging

Monday, November 2nd, 2015

Ronny found back, three years after deployment of the UvA-BiTS GPS-tracker

Wednesday, July 8th, 2015

Lesser Black-backed Gulls feed on potato crisps in Moeskroen

Wednesday, November 13th, 2013

‘Vogel het uit!’ has won the 2013 Academic Year Prize

Tuesday, November 5th, 2013

Back in Europe: UvA-BiTS Honey Buzzard photographed at the Strait of Gibraltar

Wednesday, May 15th, 2013

UvA-BiTS database passes 10 million record mark

Wednesday, May 8th, 2013

Gulls pouring into the Kelderhuispolder colony

Wednesday, April 17th, 2013

To the Karoo and back: Mate replacement & GPS tracking study of an ousted eagle

Monday, March 25th, 2013

Meeting Montagu’s Harrier Edwin in Senegal

Wednesday, March 20th, 2013

Oystercatchers: Learning how and where to survive

Wednesday, August 29th, 2012

New GPS mini-tracker facilitates investigation into movement of smaller animals

Wednesday, July 4th, 2012

Over 5 million GPS fixes in the UvA-BiTS database

Thursday, June 21st, 2012

Tagged Lesser Black-backed Gulls return to Orford Ness

Wednesday, April 18th, 2012

Gulls spotted in their over-wintering areas

Wednesday, December 21st, 2011

The UK a top vacation destination in 2011

Wednesday, July 13th, 2011

A long way from home

Sunday, June 26th, 2011

Visiting Amsterdam for a day

Saturday, May 14th, 2011

Female deserts brood, male raises chicks

Friday, May 13th, 2011

Wintering range in Sierra Leone

Friday, May 13th, 2011

Camera watches foraging Oystercatchers day and night

Thursday, May 12th, 2011

The return of a bird presumed dead

Wednesday, May 11th, 2011

Texel gulls back from wintering areas

Sunday, May 1st, 2011

First Lesser Black-backed Gull returns to the breeding colony

Monday, April 13th, 2009